Community Healing: Flamenco Dance and Mask Theatre

Julie Galle and Sandra Hughes

9th Biennial New Perspectives Flamenco History and Research Symposium hosted by the National Institute of Flamenco and funded in part by the New Mexico Humanities Council and the National Endowment for the Humanities

October 3, 2024

Watch the presentation or read it below.

View the presentation at the NIF Facebook page, talk starts at 1:52:00 >>

Presentation transcript

Julie:

I am Julie Galle. Sandra Hughes and I are joining you from Atlanta today, with our technical director who is in Colorado. On behalf of my colleague Sandra, I would like to thank the symposium committee and the National Institute of Flamenco for inviting us to join this discussion.

Emigration of Spanish flamenco artists during crises, including the Franco years and the global recession of 2008 created a flamenco diaspora, by the definition of Paul Gillroy, who describes “urgent movement” of fleeing communities (Gilroy, 207). As part of the lineage of flamenco in the United States of America, as part of that diaspora, we have folded flamenco into mask theatre productions. An analysis of methods and experiences demonstrates how flamenco has been tapped as a healing force in places in our collaboration.

Flamenco work relevant to healing

Julie:

In my early flamenco days, I heard someone refer to the art form as a ritual. This word shocked me at first but later changed my concept of flamenco from a series of recited choreographies to a breathing, evolving form of communication that didn’t tell a story as much as invite the transmission, reception, and re-transmission of emotion, in a cycle that many said was cleansing, healing. In the process of re-imagining flamenco, I explored the expectations of artists and aficionados and the aesthetics that support those expectations, in which identity is aligned with authenticity, according to the notion of historian Juan Vergillos in which, “everyone, the guitarists, singers, dancers, and palmeros, participate in the one and same feeling, and the guitarist sings, the palmeros dance, and the public rises from their seats” (Vergillos, 40).

I teach flamenco in single-semester college courses, in professional training, and to students in K-12 schools, always in a short period of time. Rather than aspiring for technical excellence or long choreographies, I impart the elements of the communal nature to my students, elements that scholars, such as José Luis Navarro and José Luis Ortiz (Ortiz, 11), traced to African and Cuban influences. I emphasize elements that speak to educators whose schools undertake initiatives of STEAM and 21st century skills, focusing on teamwork, supporting and leading, clear communication, rhythmic unity, and individual expression.

I have isolated components of interactivity, considering how they unite participants. I look at how they have evolved through time, such as African rhythms of three that changed to twos in the New World, according to Rolando Pérez Fernández. It is all so that students can experience community, expressing the individual self while acting as a group knowing anything could happen, as in Lorca’s definition of duende (Lorca, 48).

The result over the years: clients and students have commented on increased confidence, greater focus, and an emphasis on their roles as support rather than the shining star of the action. Here are some examples of that work.

Walter Benjamin wrote about aura, the existence of art in its original context. He questioned how the meaning of art changes when it is reproduced outside of its aura. Spain may be the geographic space of flamenco’s aura, but what can we say of its time in history? What can we say when flamenco moves outside of Spain? In the flamenco diaspora, flamenco artists travel from Spain to another place in the world, carrying their music and dance with them. Flamenco develops – by Spaniards and non-Spaniards – in places not in Spain.

In my experimental work, I have asked the question, if we reproduce the theory that brings together those elements to create a group identity, then could we substitute flamenco with other genres and achieve the effect of the aura of flamenco? Or, is flamenco vocabulary required to meet the expectations of the ritual of flamenco? I share short clips from three projects – that brought these questions into practice. Let’s take a look at the videos

Considering community, aesthetics, expectations, and group identity, how is flamenco a healing force, one that brings people in the audience to approach me to say they cried during a performance or that the experience was cathartic? Trauma depends on the activation of arousal, FIGHT and flight in the brain, and memories of trauma are associated with our five senses (Winfrey, XX). By hearing, the brain is programmed to react to music and call upon memory (Levitin, 83). Through my work with Sandra, I have identified specific moments in what I call the elements of interaction in flamenco – the llamadas, remates, tonal changes, all of those cues and others work to carry the brain on a journey and activate memory and emotion. I will explain that in a moment. Now let’s hear from Sandra.

Retrospective of Mask Theatre

Sandra:

My name is Sandra Hughes. It’s an honor to be included in this symposiium. Thank you, Julie, for inviting me. And thanks to all of you for joining us here today.

Safe spaces shared within a community are essential. Establishing them is a collaborative art. They facilitate gathering together to immerse ourselves in creative processes that encourage healing. We live in a time when such spaces are disappearing with little or no warning. Considering the current circumstances, what might we do to amplify and intensify the benefits offered to those who participate in arts events presented live and in person?

I’m here to share my perspectives with you as an artist with a speciality in creating mask theatre. Almost every culture has or has had masks. In a sense, I participate in the longest running show in history. From a young age I experienced the arts as a healing force while living in a society largely blind to or not believing in this reality. That society has recently changed. As part of this change Julie and I continue to explore the application of flamenco dance and mask theatre to the health, wellness and educational needs of the communities we serve.

Here’s a glimpse of my artistic world. I’m a writer, choreography, director, performer, educator and producer whose work has been consistently, ingeniously and purposely implemented, utilized, commissioned and applied by invitation as an antidote to conflict and chaos. My hosts and presenters include communities, countries, conferences and a variety of organizations ranging from major public performance venues such as New York City’s Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts to a fundraiser for the University of New Mexico’s Children’s Hospital in Albuquerque. My work has been shared locally in Atlanta, throughout the United States and globally in N.Ireland, the Republic of Ireland, Scotland, Denmark, Belgium, Spain, Germany, the Netherlands, Italy, Slovenia, Hungary, Canada and Mexico.

In my experience the ability to energize a space and put it in service to the greater good is within the reach and scope of the performing arts. What influences, abilities, commonalities and methods make this possible?

Loss is often the first influence to alert us to the need for healing. The loss of life, traditions, land, freedom and unity are some of the situations I’ve been asked to address with my work.

While performing at a Smithsonian Museum in NYC I received an unexpected invitation to serve a community in Northern Ireland located in Belfast’s endlessly violent Murder Mile. This led to six years of commissioned plays with performances for an ongoing Peace and Reconciliation Project.

An invitation to perform and teach on a small Danish Island was prompted by a fractured population divided into seven geographic factions grappling with the loss of their indigenous mask folk theatre tradition.

The invitation from behind the Iron Curtain from the Slovenian Minister of Culture in what was then Yugoslavia resulted in performances in areas of crisis in Hungary and Slovenia with a traveling audience from 25 countries to bring focus and bear witness to oppression.

At the beginning of the Pandemic the Georgia Institute of Technology invited me to speak about Art as Prescription. Soon after an organization called The Art Pharmacy invited me to become part of their programming. My classes and performances are prescribed by medical doctors, therapists and certified social workers for anxiety, depression, suicidal ideation and isolation. The effectiveness of my work is evaluated by professionals in each field. This has expanded to include homeless military veterans temporarily housed at Ft. McPherson.

Years ago a chance meeting at a resort plunged me into the world of America’s native people. A healer from the Cherokee nation in Oklahoma had come to Georgia to reclaim some of the sacred land lost to his people during the infamous Trail of Tears. He ran the stables at the resort and attended my performance there. He waited to see me afterwards and invited me to create a production that would “build a bridge between the mainstream and native cultures.” I declined saying I didn’t know enough about native cultures to do this. He insisted I travel to Tulsa to meet with the artistic director of the American Indian Theatre Company. I did so and returned to Georgia with native dance, music and cultural consultants. The production was broadcast on Public Television, performed for the live stage at Atlanta’s Woodruff Arts Center and generated years of invitations to create with and for native people.

I tell you this because for all the losses visited upon them, Native Americans know and practice some of the most potent healing methods on the planet. Their dance, music and masks are often utilized in a circular space. Seen through a non-native aesthetic these sacred sounds, actions and visuals are typically labeled art. We who heal through art often find ourselves walking a tightrope between the world of the sacred and mainstream perspectives.

Sometimes our own losses become powerful influences that create potent crucibles for healing by increasing our empathy for the suffering of others. My brother died when I was young. Art proved to be the medicine for my endless sorrow. I immersed myself in writing, dancing, acting, and music. From these pursuits I developed into a playwright, choreographer and director and managed to consistently survive the endless grief that threatened to paralyze me. Art saved my life.

Years later I arrived in New Mexico with a debilitating illness never expecting to perform again – especially in a mask – because I couldn’t breathe. My doctor said he’d never said this to anyone with this disease before, “I believe if you move to New Mexico, some place like Santa Fe, you’ll make a one hundred percent recovery.” I moved.

Soon after my arrival I received an invitation from DayStar – a legendary native choreographer. The production Sacred Woman, Sacred Earth – a moving prayer in dance and mask theatre – was performed for the Santa Fe Indian Market. Later I created a production with a Pueblo man from this cast who had a natural affinity for mask performing.

Old Man Kokopeli (photo, above) was a story about healing the grief of a Pueblo Woman who’d lost her child. It was performed at multiple venues in New Mexico including a conference at Santa Ana Pueblo for 300 native elders. It also toured throughout the United States. It took me seven years, but I did heal from my debilitating disease and I’m forever grateful to the people of New Mexico – Native, Spanish, Anglo and beyond – who supported my recovery.

I was invited to perform and teach a workshop in Scotland for members of the Findhorn Community by Findhorn Foundation member Franco Santoro. This Community is a 500 member ecovillage that has received the Habitat Best Practices award from the United Nations and is a UN training center for planetary sustainability.

At Findhorn and in other parts of Europe I’ve been considered a shaman. This is not my intention and may be a side effect of my endeavors – if a shaman is defined as “a person who journeys into the unknown to bring meaningful information and knowledge to a community”.

Michael Hickey has created hundreds of masks for my work. They’re museum quality theatrical masks handcrafted mostly out of wood with one exception. We use traditional straw mummer masks from our shared Irish culture. In this video I perform in a wooden mask representing the three faces of the moon as well as the transformation mask you just saw in the photo image.

While at Findhorn Franco taught me how to map geographic spaces for healing purposes. You can see the design here. It’s 12 sectors each with its own color with a central 13th sector. This 13th sector is the primary force that activates the other 12 (Santoro, 23).

I used this design for my productions of Water is Life – Hidden Springs, Atlanta and A Moveable Feast: Food as Culture, Commitment and Community. Another example includes the Zodiac surrounded by 12 signs as seen in the photo below.

Each sector contains specific qualities and color designations. These stay the same no matter which central animating force is selected.

Areas large and small can be mapped and purposed in this way. I’ve done this at Gateway Performance Productions’ venue The Mask Center in Atlanta where I serve as Producing Artistic Director. Mapping includes honoring the history of the land. Gateway’s Mask Center covers a natural spring, which served as a field hospital during the American civil war and as a water source for early settlers, African slaves and indigenous tribes.

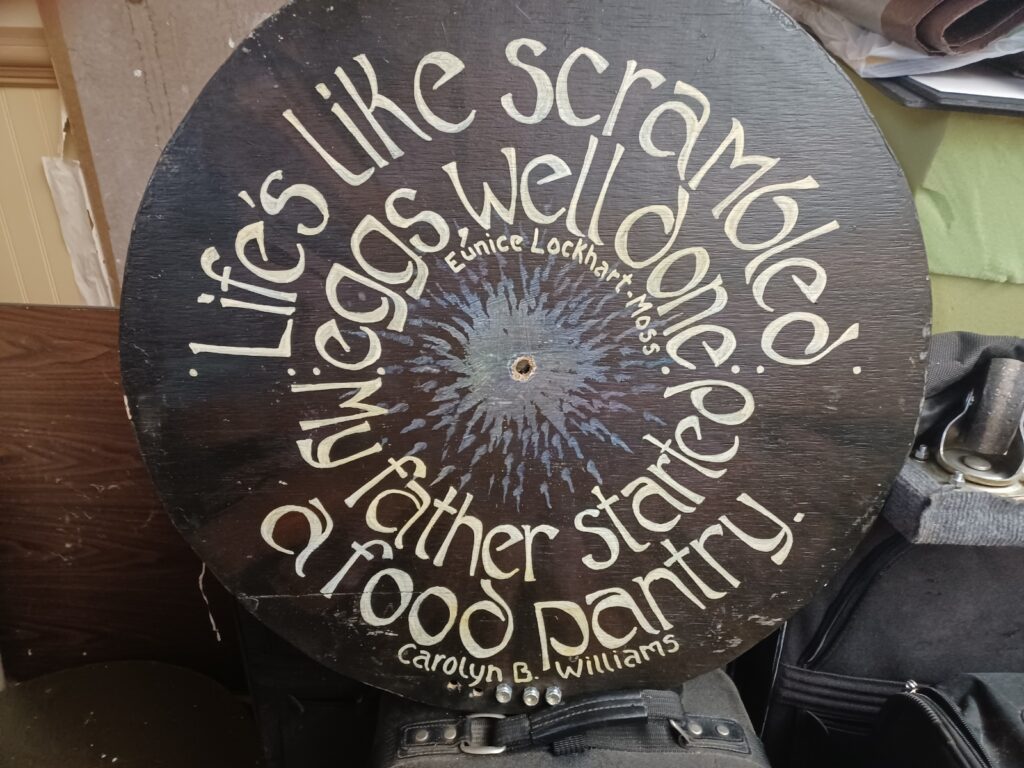

A Moveable Feast was commissioned by Atlanta’s Art on the Beltline. The project included a performance with a related large scale outdoor art installation. It combined visual art, dance, mask theatre, live music, written and spoken word and featured the work of Atlanta artists from diverse communities.

Food was donated, transported and delivered from the performance site to food deserts in the Atlanta area as an expression of the notion of “an infinite sphere whose center is everywhere and circumference nowhere.” (Hamilton, 22)

In this short video below we see a pre-performance community event outside The Mask Center in Atlanta. The central sector was dedicated to achieving community balance. Community members spontaneously named the other 12 sectors. Let’s continue to watch this video , which has no sound.

The below video shows a traditional straw mummer mask as used in one of my original plays in a community healing activity.

Mapping manifested on the ground with the area defined by 12 colorful bowls and included the innovation of vertical mapping by the art installation.

Although each of these videos features objects that define the mapping, mapping once consciously activated will be present without any external indications.

I also enlist a system of correspondences associated with hermetic philosophy, which include colors, musical tones, movements, scents, geometric shapes and textures. In this way the same emotional messages are sent to participants and reach their five senses at the same time.

Angus Fletcher is a professor of Story Science at the Ohio State University’s Project Narrative, the world’s leading academic think-tank for the study of how stories work. At OU stories are technology. And Fletcher’s neuroscience background yields unexpected creative possibilities for artists. The innovations of revered authors are viewed both as narratives and neuroscientific advancements that scientifically alleviate grief, trauma, loneliness, anxiety, numbness, depression and pessimism. Shakespeare’s Sorrow Solver invention from Hamlet contains rhythms and pacing readily adapted into movement (Fletcher, 125). Julie and I are incorporating the Bard’s invention into our current collaboration.

Dr. Joe Dispenza’s chemical dump has influenced my perspectives concerning the creation and experience of art. Human emotions release thousands of natural chemicals into the body for good or ill, according to him. (Dispenza, 29). His methods give art makers a rich avenue to explore and orchestrate into emotional landscapes.

When Julie and I met decades ago as colleagues performing and teaching for Atlanta’s Woodruff Art Center, flamenco dance was not unfamiliar to me. Early in my career I studied with Libby Lubinger – founder of the Fairmount Spanish Dance Company and attended workshops there with members of Jose Greco’s company. As part of my six years in advanced seminars taught by french mime artist Marcel Marceau I learned one of his great secrets. His style is anchored in flamenco. Achieving a flamenco “center of gravity” in the body is a must. For seven years I traveled with a professional flamenco dancer. We visited NYC, San Francisco and New Mexico for flamenco performances and to be part of this vibrant community.

Both the commonalities and differences in Julie’s work and mine have proven to be strengths.

Julie’s expertise, sensibilities and intelligence are foundational to our efforts and consistently cause them to bloom. Federico Garcia Lorca – as the central animating force in the mapping of our current project – is our Hamlet as we implement Shakespeare’s Sorrow Solver. This poet, playwright, theatre maker, flamenco aficionado and social activist like many visionaries world-wide was eliminated – sacrificed along with thousands of others by the extremists of his time. As mass killings and grief flood this world we strive to address human suffering with the balm of our emerging movement theatre productions.

Layering flamenco in Sandra’s method

Julie:

Now I will expand on how I laced flamenco elements into Sandra´s work where I thought they would meet the goals of her directions.

As we produced 24 Grievances, Sandra gave me directions to circle the stage and then begin movements that – not only expressed emotion but built the scene to the next set of emotions needed to bring the production to a conclusion.

I chose a letra of soleá por bulerías to build tension during a silence in the dialogue. I traveled in a circle as I danced, an elemental pathway in flamenco. In reflecting upon our collaboration, I realized that Sandra was asking me to activate the 12 segments of Franco Santoro´s mapping of healing spaces.

That letra I chose, with its remate, parallels the idea of correspondences of Sandra´s techniques – through the aesthetics of flamenco, everyone is united by the progression of emotional transmission and reception and re-transmission until expectations are met and a cheer of “Olé!” erupts.

I followed that letra with a very brief escobilla and subida, leaning on the idea that these tools not only speed up the tempo but change the tone of a flamenco dance solo, marking a change from one slower, often darker palo, to a faster, often lighter palo and ultimately the end. Sandra needed the work to move from sorrow and anger to optimism, as what I have termed the Yes Soliloquy, a portion of the long sentence that closes Ulysses by James Joyce, followed that footwork and subida (Joyce, 782) . Flamenco had the vocabulary that she needed. Nothing had to be invented, just repurposed, to align with the correspondences that Sandra speaks of, and to build an emotional response that Dispenza calls the Chemical Dump.

I found a similar opportunity to use what flamenco has shown me in collaborating for Dancing With Turbulence. Sandra instructed me to dance before another character was to sing in Irish. The obvious choice was a llamada, the tool that precedes the sung verse or letra in flamenco. I did not explain to Sandra the codes of these movements among flamencos. But when I finished my llamada, she signaled for the singing to begin, as if we were all in the flamenco cuadro.

I could only think of flamenco when Sandra brought up the Sorrow Solver, because as Shakespeare had engineered his ending first, dancers know how their dance solos will end. A bulerías de Cádiz will close an alegrías, a tangos will close a tarantos. From there, we make choices to direct our audiences to the ending emotional theme.

Here’s an excerpt from our proof of concept video for our current collaboration Dancing with Turbulence, which features Lorca.

Sandra:

I hope today’s talk opened up possibilities for you. We hope you found something in our presentation that will inspire your own expression of art as a healing force.

We thank you for your attention and leave you with our contact information and QR codes to access our list of works cited.

Works Cited

Benjamin, Walter. “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.” Translated by J. A. Underwood, Penguin Books, 2008.

Dispenza, Joe. Becoming Supernatural: How Common People Are Doing the Uncommon. Hay House, 2019

Fletcher, Angus. Wonderworks: Literary Invention and the Science of Stories. Simon & Schuster, 2021

Gilroy, Paul. “Diaspora.” Paragraph, vol. 17, no. 3, 1994, pp. 207–212. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43263438. Accessed 31 May 2024.

Hamilton, Ken. “The Healing Power of Presence.” Bridges Magazine, Issue 13, 2009, pp. 21-22.

Joyce, James. Ulysses. Vintage Classics Edition. New York, Vintage Books, 1990.

Levitin, Daniel. This Is Your Brain ON Music. Plume, New York, 2006.

Lorca, Federico García. In Search of Duende. A New Directions, New York, 1998

Navarro García, José Luis. Semillas de Ébano El elemento negro y afoamericano en el baile flamenco. Portada Editorial, Seville, 1998

Ortiz Nuevo, José Luis and Faustino Nuñez, La Rabia del Placer, Diputación Provincial de Sevilla, 1999.

Pérez Fernández, Rolando. La binarización de los ritmos ternarios africanos en América Latina. Casa de las Américas, Havana, Cuba, 1987.

Santoro, Franco. Astroshamanism: A Journey into the Inner Universe Vol.1, Findhorn Press, 2003

Vergillos Gómez, Juan. Libertad o tradición: una especulación en torno a la Estética del Flamenco. Aquí+más multimedia, S.L. Fundació Gresol Cultural, 1999

Winfrey, Oprah and Preey, Bruce D. What Happened to You? Conversations on Trauma, Resilience, and Healing. Flatiron Books, New York, 2021